Heat capacity of solids

In this parts of the notes, we will try to understand the historical evolution in trying to explain the heat capacity of solids. I am following ‘The Oxford Solid state Basics’ book by Prof. Steven H. Simon. If the material covered is unclear, please refer the book suggested above. In any case, go through that book. It is a lovely book to read!

Historical note: It was well known that the heat capacity per atom for a solid is given by $C \approx 3k_B$ or in other terms, molar heat capacity is $C \approx 3R$, where $R$ is the Universal gas constant. This empirical observation was known as Dulong-Petit Law.

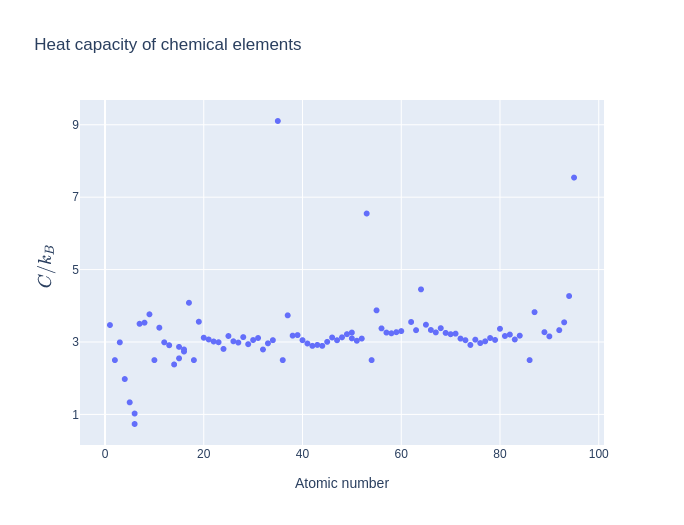

Let us look at heat capacities for different chemicals at room temperature($T = 25^oC$)1:

The above figure shows the heat capacities for various chemical elements at a temperature of 25 $^0C$ and a pressure of 100kPa. It is evident that most of them follow Dulong-Petit Law.

How do we explain this empirical observation? The answer was provided by Boltzmann using classical statistical mechanics. We will take his approach and understand the source of this empirical law.

Boltzmann approach: Classical Statistical Mechanics

The key idea in his approach was to assume atoms inside a solid to be in a harmonic potential under the influence of neighbouring atoms:

Imagine the same model with chain of such atoms forming a solid in 3 spatial dimensions(3D) at a fixed temperature T. Now, the Hamiltonian for each atom can be written as: $$ \mathcal{H}(\mathbf{q},\mathbf{p}) = \frac{\mathbf{p}^2}{2m} + \frac{1}{2}m\omega^2\mathbf{q}^2$$

Note:

- We assumed the spring constant to be same in all three dimensions.

- Quantities $\mathbf{p}$ and $\mathbf{q}$ are three dimensional vectors.

Since we have a large collection of such atoms at a fixed temperature T, we can find its energy and heat constant using classical canonical partition function. The single-particle partition function is given by, $$ Z_1 = \frac{1}{h^3}\int\int e^{-\beta \mathcal{H}(\mathbf{q},\mathbf{p})}d\mathbf{q}d\mathbf{p}$$

We shall explicitly evaluate this quantity. It will be handy to recall the Gaussian integral of one variable: $$\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{-ax^2}dx = \sqrt{\frac{\pi}{a}}$$

Let us get our hands dirty!

$$Z_1 = \frac{1}{h^3}\int\int e^{-\beta(\frac{\mathbf{p}^2}{2m} + \frac{1}{2}m\omega^2\mathbf{q}^2)}d\mathbf{q}d\mathbf{p} \ = \frac{1}{h^3} \int exp{\frac{-\beta\mathbf{p}^2}{2m}} d\mathbf{p} \int exp{\frac{-\beta m\omega^2}{2}\mathbf{q}^2} d\mathbf{q} $$

We can further separate the 3D integral into a product of three 1D integrals in both momentum and position coordinates.

$$ \begin{align} Z_1 = \frac{1}{h^3} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta{p_x}^2}{2m}} dp_x \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta{p_y}^2}{2m}} dp_y \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta{p_z}^2}{2m}} dp_z \\\ \text{x} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta m\omega^2q_x^2}{2}} dq_x \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta m\omega^2q_y^2}{2}} dq_y \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta m\omega^2q_z^2}{2}} dq_z \end{align} $$

$$= \frac{1}{h^3} \left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta{p_x}^2}{2m}} dp_x\right]^3 \left[\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} exp{\frac{-\beta m\omega^2q_x^2}{2}} dq_x\right]^3$$ Using the 1D Gaussian integrals above, we get

$$ Z_1 = \frac{1}{h^3} \left[\sqrt{\frac{2\pi m}{\beta}}\right]^3 \left[\sqrt{\frac{2\pi}{\beta m \omega^2}} \right]^3 = \left[\frac{k_B T}{\hbar\omega}\right]^3$$ where $k_B$ is the Boltzmann constant and $\hbar = h/2\pi$. The N particle partition function can be obtained by assuming that the particles are distinguishable: $$Z_N = [Z_1]^N = \left[\frac{k_B T}{\hbar\omega}\right]^{3N}$$

We know, from the connection to thermodynamic quantities, the internal energy of this system can be obtained by $$ E = -\frac{\partial}{\partial\beta}lnZ_N = 3Nk_BT$$

Thus, the heat capacity per atom is $$C_v = \frac{\partial}{\partial T} \frac{E}{N} = 3k_B$$

Hooray! We have obtained our result of $3k_B$ for the specific heat. Boltzmann’s idea worked and we can now explain this empirical observation. Thus, Boltzmann accounted lattice vibrations as the source for the heat capacity and modelled it classically as masses connected by a spring.

Is it the end of the story? Even the graph above will tell you that there are outliers to this empirical law. Particularly, heat capacity of diamond deviates from Dulong-Petit law at room temperatures. Also, heat capacity strongly depends on temperature, and becomes smaller at lower temperatures(Apparently room temperature is a “low” temperature for diamond). What are we missing here? Einstein came up with a brilliant idea to consider quantum mechanics as the key here.

Einstein’s approach: Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

Einstein followed a similar approach to that of Boltzmann except, he used quantized harmonic oscillator levels for each atom, given by $$\epsilon_n = \hbar \omega(n+3/2)$$

where $n = n_x+n_y+n_z$. The partition function in this case in given by: $$ \begin{align} Z_1 &= \sum_{n_x,n_y,n_z\geq0}e^{-\beta \epsilon_n} = \sum_{n_x,n_y,n_z\geq0}e^{-\beta \hbar \omega(n_x+n_y+n_z+3/2)} \\\ &= e^{-3\beta \hbar\omega/2}\sum_{n_x\geq0}e^{-\beta\hbar\omega n_x} \sum_{n_y\geq0}e^{-\beta\hbar\omega n_y} \sum_{n_z\geq0}e^{-\beta\hbar\omega n_z} \end{align} $$

Each sum represents a geometric series and thus reduces to $$ Z_1 = \left(\frac{e^{-\beta \hbar\omega/2}}{1-e^{\beta \hbar\omega}}\right) \left(\frac{e^{-\beta \hbar\omega/2}}{1-e^{\beta \hbar\omega}}\right)\left(\frac{e^{-\beta \hbar\omega/2}}{1-e^{\beta \hbar\omega}}\right) = \left[\frac{1}{2sinh(\beta\hbar\omega/2)}\right]^3$$

The N particle partitions function is thus given as $$Z_N = \left[\frac{1}{2sinh(\beta\hbar\omega/2)}\right]^{3N}$$

and energy $$ E = -\frac{\partial}{\partial\beta}lnZ_N = 3N\frac{\hbar\omega}{2}coth\left(\beta\hbar\omega/2\right) = 3N\hbar\omega\left(n_B(\beta\hbar\omega) + \frac{1}{2}\right) = 3NE_1$$

where $n_B(x) = \frac{1}{e^{x}-1}$ is the Bose occupation factor. The quantity $E_1$ stands for energy of a single harmonic oscillator in 1D and it can be interpreted as $n_B$ bosonic modes of energy $\hbar \omega$ are occupied.

The heat capacity per atom can be similarly obtained as above: $$C_v = \frac{\partial}{\partial T} \frac{E}{N} = 3k_B(\beta\hbar\omega)^2\frac{e^{\beta\hbar\omega}}{(e^{\beta\hbar\omega}-1)^2}$$

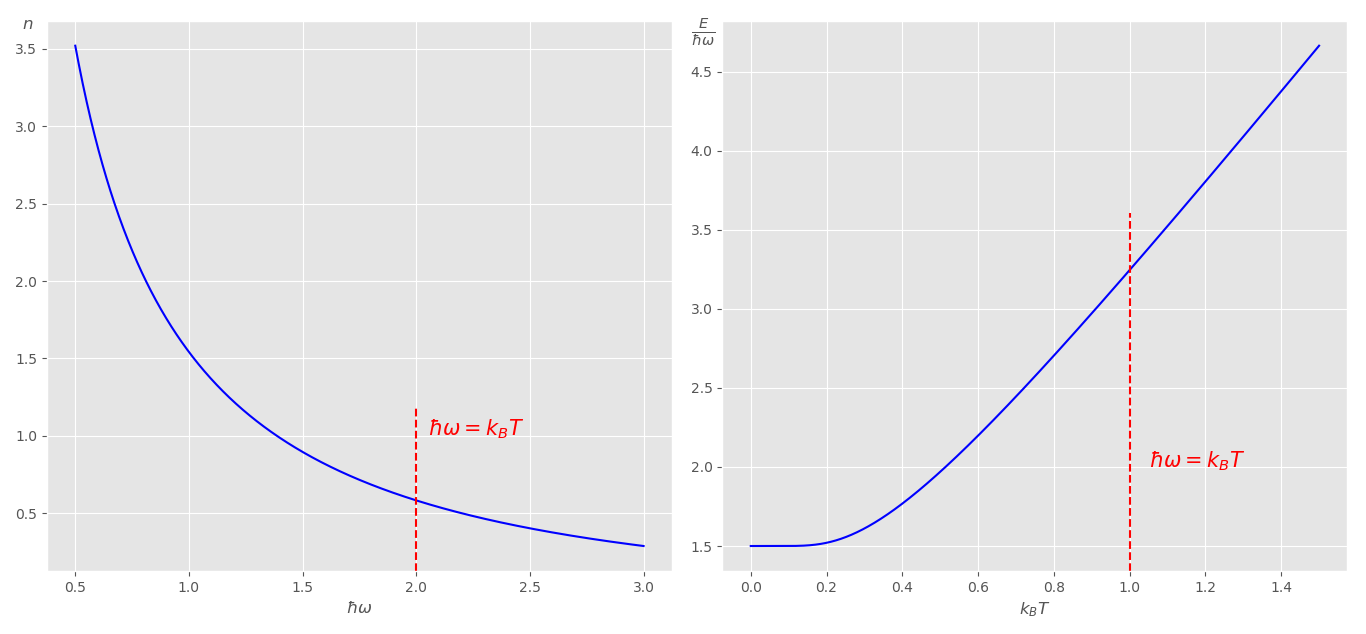

Obervation: The plot on the left tells us that lower energy modes have higher occupation than the higher energy modes. The plot on the right gives us the energy as a function of time. It shows us that as $K_BT\ll\hbar\omega$, the heat capacity, which is the slope, tends to zero.

This can be further verified by explicitly working out the heat capacity per atom: $$C_v = \frac{\partial}{\partial T} \frac{E}{N} = 3k_B(\beta\hbar\omega)^2\frac{e^{\beta\hbar\omega}}{(e^{\beta\hbar\omega}-1)^2}$$

The expression above might not be intuitive at first sight. We can check whether we obtain Dulong-Petit law in the high temperature limit: $K_BT \gg \hbar \omega$ $$ \frac{\hbar\omega}{K_BT} \ll 1 \implies \text{exp}(\frac{\hbar\omega}{K_BT}) \approx 1 \ \implies (e^{\beta\hbar\omega}-1) \approx \beta\hbar\omega \quad(\text{using Taylor expansion of exponential}) $$

Using these approximations, the high-temperature asymptotic behaviour of heat capacity reduces to $C = 3K_B$. We have managed to recover Dulong-Petit Law!

Similarly, we can obtain the low temperature limit: $K_BT \ll \hbar \omega$ $$ \frac{\hbar\omega}{K_BT} \gg 1 \implies \text{exp}(\frac{\hbar\omega}{K_BT}) \gg 1 \ \implies (e^{\beta\hbar\omega}-1) \approx \text{exp}(\frac{\hbar\omega}{K_BT}) $$ Using these approximations, the low-temperature asymptotic behaviour of heat capacity reduces to $$ C_v = 3k_B(\beta\hbar\omega)^2e^{-\beta\hbar\omega} $$

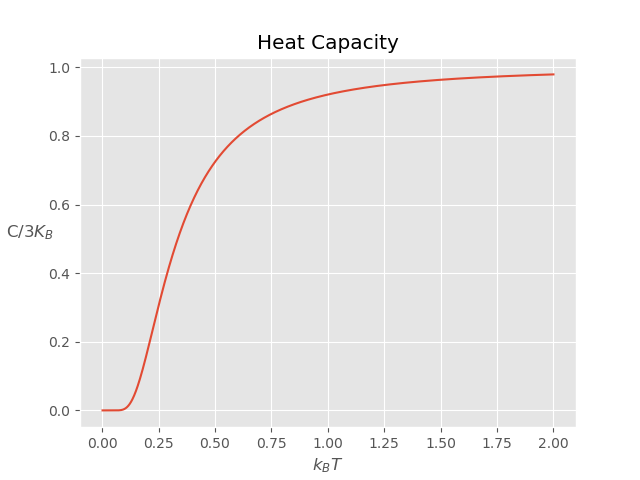

We see that heat capacity drops exponentially as we lower the temperature. All our findings, can be captured by plotting heat capacity as a function of temperature:

This exponential drop can be understood by looking at the energy spectrum of each atom. As we lower the temperature below the characteristic energy, i.e., $k_BT < \hbar\omega$, all atoms start occupying the ground state or low lying states according Bose distribution. Since the spectrum is discrete, the thermal energy is not enough to keep them in higher states and energy drop is higher(exponential).

Thus, the Einstein’s model qualitatively captures the low temperature behaviour of heat capacity in solids. Let us look at how it performs quantitatively and compares with a experimental data.